A Famous First Line That Gave Birth To A Novel

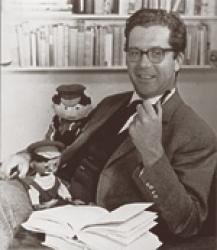

Writing Jim Button was the start of Michael Ende’s literary adventure.

Writing Jim Button was the start of Michael Ende’s literary adventure. For eighteen months Michael Ende struggled to find a publisher for his five-hundred-page novel Jim Button.

For eighteen months Michael Ende struggled to find a publisher for his five-hundred-page novel Jim Button.Michael Ende often spoke of how his first novel Jim Button came into being. ‘I sat down at my desk and wrote: “The country in which the engine-driver, Luke, lived was called Morrowland. It was a rather small country.” Once I’d written the two lines, I hadn’t a clue how the third line might go. I didn’t start out with a concept or a plan - I just left myself drift from one sentence and one thought to the next. That’s how I discovered that writing could be an adventure. The story carried on growing, new characters started appearing, and to my astonishment different plotlines began to weave together. The manuscript was getting longer all the time and was already much more than a picture book. I finally wrote the last sentence ten months later, and a great stack of paper had accumulated on the desk.’

Michael Ende always said that ideas only came to him when the logic of the story required them. On some occasions he waited a long time for inspiration to arrive.

At one point during the writing of Jim Button the plot reached a dead end. Jim and Luke were stuck among black rocks and their tank engine couldn’t go any further. Ende was at a loss to think of a way out of the adventure, but cutting the episode struck him as disingenuous. Three weeks later he was about to shelve the novel when suddenly he had an idea - the steam from the tank engine could freeze and cover the rocks in snow, thus saving his characters from their scrape. ‘In my case, writing is primarily a question of patience,’ he once commented.

After nearly a year the five hundred pages of manuscript were complete.

Over the next one-and-a-half years he sent the manuscript to ten different publishers. Each responded with a rejection slip: ‘Unsuitable for our list’ or ‘Too long for children’. Ende even wrote to Erich Kästner but received no reply. In the end he began to lose hope and toyed with the idea of throwing away the script. At the time he and Ingeborg Hoffmann were in the middle of a three-month separation period designed to test the strength of their relationship. When she heard of his problems, she called time on the separation and decided to take the initiative. Sammy Drechsel, head of cabaret group Die Namenlosen (‘The Nameless Ones’), advised her to try a small family publishing-house, K. Thienemanns Verlag in Stuttgart. Michael Ende’s manuscript landed on the desk of company director Lotte Weitbrecht who liked the story and decided to accept it. Her only stipulation was that the manuscript had to be published as two separate books.

Curiously enough Michael Ende was never re-united with the illustrator who had set him on his literary path. He couldn’t even remember his name.